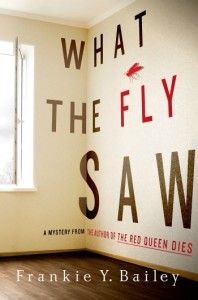

The following is a guest post by Frankie Y. Bailey, author of What the Fly Saw. If you would like to write a guest post on my blog, please send me an e-mail at contact@cecilesune.com.

When I was an undergrad at Virginia Tech, I had a double major in Psychology and English. I was lucky enough to have the opportunity to study the complete works of Shakespeare with a terrific professor. I came out of that experience with lines from the plays and sonnets committed to memory and enough plot ideas to fuel my writing efforts. I also had learned to appreciate what a villain can bring to a literary work or a film. Macbeth intrigued me more than Hamlet. Both were tragic heroes, but Macbeth was a man of action. True, his wife, egged him on (and paid dearly for her ambition). But Macbeth, the hardened warrior, did not dilly-dally about his decisions as much as the melancholy Dane. Hamlet might have been cleverer, but a little “to be or not to be” goes a long way. My heart broke for Macduff, when his wife and children were slain, but Macbeth had some of the most quotable lines (“Lay on, Macduff”). Richard III (who may have been maligned) and Iago (slimy and malicious) are both memorable. Studying Shakespeare, I learned a basic truth: “That one may smile, and smile, and be a villain.” Okay, that was one of Hamlet’s better lines. But Hamlet’s opponent, Claudius, murderer and a usurper, has never struck me as a particularly worthy foil. He is corrupt but a coward, and hardly a challenge once Hamlet makes up his mind.

This ability to captivate is why Hannibal Lecter – although he isn’t my dish of fava beans – captures the imagination of readers and movie buffs. In the film version of The Silence of the Lambs, Anthony Hopkins is a superb villain. He is much more interesting than the serial killer that Clarice Starling, the young FBI trainee, is pursuing. Lecter sends a chill down the spine. Without Hopkins’s Hannibal Lecter, Jodie Foster’s equally superb performance as Clarice Starling would not shine as bright.

Having said all this, I have to confess that this post is a reminder to myself that my protagonist should always be as interesting as any villain I might create. One of the most challenging tasks I’ve ever had as a writer was when one of my protagonist, crime historian, Lizzie Stuart, went looking for her long-lost mother. Her mother, Becca, turned out to be a complex character who required Lizzie to up her game. I had so much fun writing Becca that I hated for the book (You Should Have Died on Monday) to end. Well, not really – that first draft took a lot out of me. And I was relieved to get to the end and discover that Lizzie had held her own and not been diminished by a woman who was not exactly a villain, but definitely not a loving mother.

I had this matter of intriguing villains in mind when I created Hannah McCabe, the Albany, New York police detective, who has appeared in two novels, The Red Queen Dies (2013) and What the Fly Saw (2015). The books are set in the near-future, 2019 and 2020, respectively. This fictional world is much like the one we live in – except for an event that I’ll mention in a moment. The books are traditional police procedurals. The villain isn’t revealed until the end. But during her investigation, McCabe deals with the havoc that the killer has caused.

In the McCabe books, there is another villain, a third party right-wing presidential candidate named Howard Miller. He is not present, but with an election looming, his campaign is a source of anxiety. And then there is that UFO that appeared over the Mojave Desert back in 2012. Fighter jets scrambled, and the UFO disappeared in a blinding flash of light. No aliens have arrived. The McCabe books are mysteries, not science fiction. But I wanted to deal with social issues at the tipping point (the reason for moving into the near future). Since the present has a way of catching up with the future, I added this twist to create an alternate universe.

In the McCabe books, there is another villain, a third party right-wing presidential candidate named Howard Miller. He is not present, but with an election looming, his campaign is a source of anxiety. And then there is that UFO that appeared over the Mojave Desert back in 2012. Fighter jets scrambled, and the UFO disappeared in a blinding flash of light. No aliens have arrived. The McCabe books are mysteries, not science fiction. But I wanted to deal with social issues at the tipping point (the reason for moving into the near future). Since the present has a way of catching up with the future, I added this twist to create an alternate universe.

In this fictional world, people have responded in various way to chronic uncertainty. Those like Hannah and her police colleagues have gone on doing their job. But the survivalists take to their bunkers each anniversary of the UFO sighting, expecting an armada to arrive. And the young “space zombies” (my version of 1960s hippies) have dropped out with drugs, horror movies, and Rod Serling’s “Twilight Zone”. As McCabe observes, in the “Twilight Zone” episodes, ordinary humans engaged in acts of villainy when frightened. Ordinary humans may not be as interesting or intriguing as Macbeth or Hannibal Lecter, but even the dullest among us have the capacity to be dangerous. McCabe tries to keep that in mind.

About the author and her work: Frankie Y. Bailey’s Website.