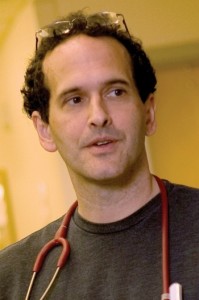

The following is a guest post by Raymond Barfield, author of The Book of Colors. If you would like to write a guest post on my blog, please send me an e-mail at contact@cecilesune.com.

I graduated from medical school in 1993 and from residency in 1996. Work hour limits for medical students and residents were established in 1997 (the new rule was that students and residents can work no more than 80 hours per week). I mention that only to say that the fact that I wrote nearly every day, except Sundays, during medical school and residency points to how important writing was, and is, in my life as a doctor. I have many questions about the relationship between writing and medicine. I’m still not sure why writing helps me survive being a doctor, nor why being a doctor helps me survive being a writer. I just know that it is true. The deepest moments of being a doctor and the deepest moments of being a writer feel similar to me. The hardest moments and the funniest are also similar, and they often happen at the same time. Whatever outward signs of authority medicine claims for itself—white coats, corridors with ‘Do Not Enter’ signs, and promises of various tenuous miracles—doctors are often lost, if they have any sense about them. Or lost-ish. I think the same is true for writers. Who can meander day after day on the threshold of mystery, fragility, death, and God, and not be at least a bit bewildered?

In both writing and doctoring, words must be honed into a manageable shape that does some kind of work in the world. That is the only way words get turned into a novel, and it is the only way words get turned into a story that can actually guide the decisions a doctor makes with an ill or dying person. Both of these disciplines depend on understanding how words stop just being ‘more words’ and become a story. So what is a story?

My grandfather, who had an eighth grade education, was a great story-teller. He figured out what a good story is by telling and listening to thousands of them. He knew that every great story starts with a “Once upon a time…” along with some details to give the listener a sense of what normal life looks like. But before long, if the story is any good, something has to disrupt normal life. A big, bad wolf needs to show up, or some greedy company needs to dump toxins in the creek where everyone in town fishes on weekends. In any case, it needs to cause enough trouble to lead to one problem after another. The first part of the story helps you understand why the disruption and all the problems that follow matter. You have to know what’s been lost or else you don’t know what to hope for.

When I walk into a patient’s room, if I’m doing my work well, I listen for their “Once upon a time.” I need to know who they are because I am about to be the disruption in their story, and since I am an oncologist the disruption is usually pretty rough. There is life before I say, “Those funny looking cells your doctor saw … I am sorry to say that those are leukemia cells,” and then there is life after that, with lots of challenges that they never asked for, but that they must try to overcome if they are ever going to find home again. Eventually, the patient is either cured or not cured. In either case, the story is not over. The end of the story needs to show what they do in response to their altered world.

So much is revealed in this final part of a story as patients (and characters) live out the consequences of all that has gone before. Often the stories are going to be much shorter than anyone thought, so the stakes are high. A doctor who is paying attention to high-stakes story crafting like that learns just how much stories matter. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end to every life, and like stories, some lives are long, some are medium, and some are very short. No matter how long or short it is, it matters. My patients lose their hair, they vomit, they have limbs cut off, and they become sterile. And often they are cured. But every patient’s life is a whole life, and I have been witness to astonishing beauty in the middle of suffering.

Doctors and writers both name things that matter, and the words they choose are important for helping to shape the experience of patients. When I name ‘the problem’, whether in a novel or in a family conference, I give it a substance and a status that it didn’t have before. I show its contour so that it can be a topic of conversation among family and friends: “Honey, the doctor figured out what’s going on … here’s what’s happening.” And like any story, once the antagonist is named, everything after is affected.

Words make things happen. They can make a life better or worse. They can make the human heart feel courage, or sadness, or joy, or hope. They can make a person feel worthless, and they can rescue a person. The world of medicine is not built with shiny machines, knives, and bags of Latinate-named intravenous fluids. Those things are part of medicine, but the world itself is made up of stories that situate the person, account for the past, impact the future, and offer a sense of what to do next.

William Osler said, “It’s much more important to know what sort of patient has a disease than to know which disease a patient has.” I tell my residents to stay curious about the lives of their patients if they want to become great doctors. When I am alone in my study writing, I do the same. For my patients, story telling in the hospital is literally a matter of life and death. If their stories don’t get told well, all sorts of terrible things can happen. But for some reason writing stories in my study also feels like a matter of life and death. Even if I can’t give a better account for why that is, I know that I would be a fool to ignore it.