The following is a guest post by Rebecca Burns, author of The Settling Earth. If you would like to write a guest post on my blog, please send me an e-mail at contact@cecilesune.com.

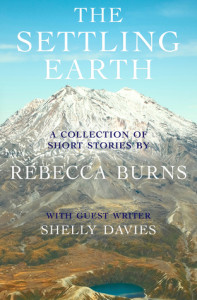

The expansion of empire in the nineteenth century brought wealth to Britain, and also a number of challenges and opportunities. One such opportunity was emigration – movement into colonies such as Australia, South Africa, Canada and New Zealand widened the options open to potential emigrants. My book, The Settling Earth, is a collection of short stories that fictionalises the experiences of settlers who travelled to New Zealand and attempted to make this strange new land their home.

The emigrants making the three month crossing from British ports to Auckland, Wellington and Lyttleton were as varied as the baggage they brought with them, and the multitude of characters in The Settling Earth reflects that. Young, newly married women emigrated with their husbands (as Sarah did in the collection’s first story, “A Pickled Egg”); single or widowed women with few options back home took a leap into the unknown (just like Phoebe in “Miss Swainson’s Girl” and Mrs Ellis in “Tenderness”); while others emigrated with their families and built homes for themselves in the bush or on the wide open Plains of the South Island (as Frances did in “Ink and Red Lace”). And, yet, while the emigrants themselves varied and their responses to the new landscape and challenging environment differed, the pain of leaving families behind in England – perhaps never to see again – must surely have been shared.

The anguish of separation is a theme that runs throughout The Settling Earth. Sarah, the central character in “A Pickled Egg”, lives on an isolated sheep farm in Canterbury, South Island, and muses upon the twists and turns her life has taken to lead her to New Zealand. She aches for her family. Photographs of her parents “rested on a table next to her side of the bed. She could turn and look at them each morning, or even when she felt lonely, and imagine they were with her.” Such longing for relatives was shared by other, real-life emigrants. Painted miniatures, portraits and photos were precious mementos for settlers, providing a valuable connection to much-missed family members.

Of course, settlers wrote home to their families, describing their new lives. Yet, in the first years of settlement, it was not uncommon for letters to take several months to reach New Zealand, and there are sad stories contained in the archives of letters arriving several months after the writer – a relative – had died. The Settling Earth portrays the impact of a similar, life-changing piece of news imparted in a letter in the story “Port and Oranges”. Miss Swainson, the central character and owner of a brothel in which other characters from other stories work, receives a letter from England, asking her if she would give up her New Zealand life and return to help her family: “[…]the missive from England sat on top. An answer was required, a decision must be made. That much, at least, was clear from her sister-in-law’s terse prose. Miss Swainson could not help but smile. How she must have hated writing it!”

Miss Swainson is faced with a decision that other emigrants must also have faced and, of course, some settlers did return home to England. They were driven by either disappointment with their lives in New Zealand, a change in circumstances, or an overwhelming desire to reunite with family. But many stayed, overcoming the isolation of pioneer townships or bush living, forging homes and raising families, and creating a new society. The stories in The Settling Earth portrays this in fiction, showing how a group of settlers attempted to do just that, and the challenges they faced.

About the author and her work: Rebecca Burns’ Website.