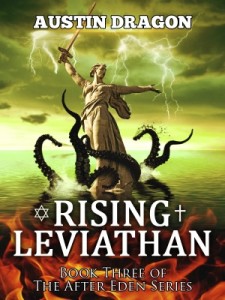

The following is a guest post by Austin Dragon, author of Rising Leviathan. If you would like to write a guest post on my blog, please send me an e-mail at contact@cecilesune.com.

Is our future a happy, shiny “Star Trek” one or a grimy, hellish “Blade Runner” one?

There was a time when Greece ruled the known world. Egypt was the center of Christianity. The Roman Empire was the greatest empire ever and would last until the end of time. Great Britain was the most powerful nation the world had ever seen and would easily crush the Thirteen Colonies. The Nazis were destined to take over the world. Any day now, World War III would erupt between America and the Soviet Union. Well, none of these turned out to be true.

My science fiction and international After Eden thriller series, among other things, maneuvers through our future seventy-five years from now, from America, Mexico, Australia, Canada, and with the latest book, Rising Leviathan (Book #3), Russia, India, and the Middle East. That world is amazing and wonderful, but also terrifying and disturbing. Some of that future is expected, but much of it is not—though with a bit reflection, it too seems inevitable and prophetic.

Leaving our own personal world-views aside, the question is: Which science fiction writers are right? The ones who subscribe to a Star Trek future where there is bad, but humankind evolves beyond greed, bigotry, and oppression to collectively pursue noble endeavors with an amazing array of advanced science and technology. Or are the science fiction writers who reject such Pollyannaish notions for a world where all the vices of humankind are on full display and the science and technology is used for every kind of thing other than goodness and the benefit of mankind.

Books (and by proxy movies and plays) can help us ask those questions that we might not otherwise reflect upon. We do have to ask ourselves these questions not as book-lovers, but as people, citizens of our respective countries, or inhabitants of this planet. Is utopian science fiction denying what humans are and dystopian science fiction being realistic and honest? Or are dystopian writers just a bunch or morose, “the glass is half empty,” kind of people who will never acknowledge humanity’s ever-forward march to being better, despite natural setbacks.

In the world of my After Eden, America is in majority militant-atheist with Jews and Christians living in segregated enclaves, Western Europe is gone—assimilated by the Supreme Islamic Caliphate, China and India have merged to form a mega-superpower (though China runs its alliance), Eastern Europe has merged with Russian out of pure survival, and all the other regions are minor players at best. Cities are called tek-cities because they are so automated (artificial intelligence) that they are more computer than construction, auto-drive cars, drones everywhere, police storm troopers, robot pets, cyborgs, Vampires, Vulcans, and Jedis (official religions), “body farms” to grow human organs, human cloning, and the science to create quasi-life (for military purposes). All drugs are legal, there are six recognized genders, all marriage is legal (though it has gone full circle to only religious people marry), rampant suicide, anarchistic terrorists have surpassed Islamic ones in carnage; class divisions are non-religious versus religious, and those who live in tek-cities versus those who live in the Outlands and beyond. Quite a world they have. And it all leads to World War III—or the first global war of the Tek Age.

Some would say I fall squarely on the dystopian science fiction side of the face. I would disagree. I’m not a pessimist. I am working on new science fiction series—one cyberpunk and the other hard science fiction—and they are so much more complex than that. Actually, my natural state is optimism and idealism. However, what trumps it all is that I’m a realist. To give both a political and non-political example here in America, the reason so many significant problems don’t get truly acknowledged, addressed, or ever solved is not because of liberals and Democrats, or conservatives and Republicans. The reason is the largest voting group in America, growing by leaps and bounds. It is the group that doesn’t vote. Or even more precisely, those who are disengaged and there is nothing you can do to make them engage.

Science fiction, more than any other genre, allows us writers to present those alternative futures to audiences. Whether shiny with lots of eye candy or in grimy, desolate settings; some of it is quite bad in its writing, very bad. Some of it only exists to cash on some hot trend (like the current “young adult” wave). But the good science fiction is so much more than that. It is yelling at us that there is a possible outcome for us that we really, really, really want to avoid. And then there is the voice that says maybe we can’t avoid that outcome. Ancient Egypt and Greece were conquered. Ancient Rome and Great Britain declined. Aren’t we really saying that civilizations–because they’re run by people–will inevitably decline no matter what, whether it’s two hundred years or twenty thousand years from now?

I actually am in the center on this debate. Our natural path is a dystopian one. But we can get to a utopian one if we fight for it—hard. That’s how it’s always been. Will we fight for it? Honestly, I believe not. Not because we don’t want to or we are inherently bad or are incapable of it. It’s we are the generations that didn’t have to fight for what we have. We are their descendants. We’ll fight…when we lose it. Even though it would be so much easier, cheaper, and better not to have lost it at all and find ourselves in one of those dystopian science fiction stories.

About the author and his work: Austin Dragon’s Website.