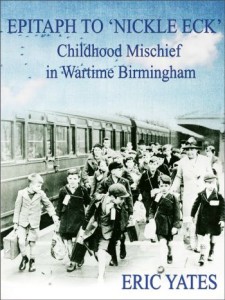

The following is a guest post by the publisher of Eric Yates, author of Childhood Mischief in Wartime Birmingham. If you would like to write a guest post on my blog, please send me an e-mail at contact@cecilesune.com.

About the Book

This treasure trove of Second World War stories are a must read for those wanting to know about the lives of ordinary families in the history of Britain – or indeed, anybody wanting a good laugh to brighten up their day.

In the history of Britain there is a shortage of Second World War stories detailing the lives of ordinary families living in poverty, the children’s games and the black market profiteering that history has forgotten.

The story of young Eric and John is here to set the record straight. Two boys growing up in the midst of rationing, with a flair for mischief and a sense of humour history will never see again – what could happen? Quite a lot, apparently, if the exciting family life of Eric and John is anything to go by. Telling of their family life in war torn Birmingham where poverty was rife, John’s account is full of wit and the kind of humour history should remember. From the infamous Bread Pudding Incident to the charming children’s games like ‘Penny on the Brick’, you will find laughter and warm memories of time spent in an age before computers, when children had to entertain themselves. Yet there is poignancy here, too, as Eric and John find themselves swept up in the greater tide of war as evacuees, made to travel to the country with no chance of looking back…

Excerpt

Rationing has often, rather loftily, been written about as a great victory for British organisation and our great sense of ‘Fair play’. Where I came from it was a glorious opportunity for barter, black-marketing and profiteering.

Petrol was King, as very little was allocated to the private sector, mainly for doctors and similar professionals. Other recipients were skilled engineers in reserved occupations such as our Dad, a toolmaker, who owned a pre-war Jowett – an unusual possession for a working-class family on a Council Estate. Petrol coupons were almost priceless and a subindustry of petrol siphoning soon emerged. Unwary small children were taken out at night by their elder brothers, equipped with a can and a length of hosepipe (readily available cut from stirrup pumps which proliferated in wartime). A victim’s car would be pre-selected in an unlit street and the hose inserted into the tank, facilitated by the lack of cap-locks or double bends leading to the tank. The youngster would then be given the free end and told to suck hard and push the end into the can when the fluid flowed. This instruction was somewhat superfluous as the watching elders grabbed the hose when the child’s eyes opened wide, his face turned a funny colour and he began to choke. A gallon of petrol gained this way was easily sold – sometimes for a whole pound note, a week’s beer or a yard of knicker elastic.

The penalty for this type of theft was severe, which is where Epitaph to ‘Nickle Eck’ 10 the use of a disposable urchin came in. If the scavengers were disturbed they fled in different directions leaving the child, coughing and retching, to ‘carry the can’. He would be too young to be prosecuted – and probably too ill to testify.

Another source was Industrial petrol, available to essential haulage vehicles and from agricultural equipment. This fuel was dyed a reddish-pink colour and was easily identified if used in private cars, but this did not preclude many embryonic alchemists in Birmingham from adding their favourite ingredient to metamorphose it into liquid gold. Of course there were many accidents, as the highly inflammable mixtures metamorphosed the mixers and their garages into ashes. But, such is progress…

There were many illegalities during the war but we never ran short of rationed items. Our Uncle Alf, Mom’s brother, drove a fire engine so petrol coupons for fuel were available to him at all times for such a crucial vehicle and he was never questioned. To conserve fuel all private cars were limited by law to a few coupons each month, but Dad never ran short. Another of Mom’s brothers, Uncle Arthur, was a pig farmer living in Coleshill. Meat was restricted to food coupons, as were almost all other food items, but Uncle Arthur would smuggle a piglet into a hidden sty and slaughter it for all the family so there was no shortage of meat – especially at Christmas.

Rationing worked splendidly if the families of a working class council estate understood the basic premise, which was flawed. Bread was not rationed and few families could eat all the bread allowed, but distribution was restricted to only one daily delivery and Mom made sure our family was always at the front of the queue. Therefore, if a family needed extra bread we, the Yates’s, honed in on them and began to barter. Mom found that a local family, named Jebb, were supreme champions at eking out the meagre tea ration – which was based on the little-understood fact that very little tea was grown in England, especially in Birmingham.